Buddy and Melissa Stockwell cruise aboard Indigo Moon, a Lagoon 380 (38’) catamaran hailing from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA. They set off on New Years Day 2005 and returned to put the boat for sale Sept 2010. They spent that time cruising the US East Coast and the entire Caribbean: 18,749 miles in 5.5 years. You can find more information including bios and published articles on their

website.

How would you recommend that someone prepares to cruise?

There were two main categories of preparation for us: 1) sailing skills to be able to deliver our vessel safely to distant shores; and 2) recreational skills to provide us with the ability to really enjoy the lifestyle and the destinations. As far as sailing skills, I have to say that from what we saw out there cruising for over five years, it does not take much experience and “book learning” to be ready if you are physically fit, agile, are coordinated, and have an intuitive mechanical aptitude as well (I call it the “McGyver Factor”). We saw many people buy boats, even huge million-dollar catamarans, and set out totally “green” and do perfectly well because they had great natural aptitudes; within a few weeks and months of full time cruising they were way more skilled than that resident “know-it-all” down at your local marina. On the other hand, one couple we met had read all the books, took all the courses, and even had a fine large sailing yacht built brand new, but their adventure was not fun at all. They encountered mishap after mishap, and even broke some bones in the process. Within two years they were through. So, as cruel as it sounds, a very large degree of real success as a cruiser comes from natural physical and mental aptitudes and not classes and courses and books.

Cruising is a very physical endeavor and being “young” and agile with good reflexes at whatever age you are plays a huge role, as you might imagine. That said, across the board as to all new cruisers, the only thing you can really screw up at first is not waiting for really calm weather windows to get to know your limits and the boat’s limits slowly. Stick to coastal cruising and moving in very good weather when first starting out. Never ever be on a schedule. Be patient. Go slow, literally and figuratively. Also, make sure to take turns and rotate all jobs until all crew can single hand the boat and get home in an emergency. It’s best for a couple to alternate days as captain and deckhand. When you begin cruising full time, you’ll learn faster than you think while in the company of others in the cruising community. In the meantime, all you have to do is not get hurt and not hit anything with the boat. In the fullness of time, the rest of cruising will take care of itself if you have any common sense. It’s just that simple. As for recreational skills, get in physical shape! Be ready to hike and bike and walk for miles and miles to provision, etc. I would also strongly recommend getting certified to SCUBA dive so that you can make the most of those exotic destinations.

In your own experience and your experience meeting other cruisers, what are the common reasons people stop cruising?

There are two categories: 1) the natural, average lifespan of cruising; and, 2) superseding and intervening events that will most-likely to send folks home early. As for the natural lifespan of cruising, this totally freaks out all the romantics who envision “sailing off into the sunset forever.” But it is a fact: cruising is not a forever, end-all adventure for most people. Ninety percent of the Caribbean Fleet we sailed with, and knew personally, has sold their boats too, and we are all happily on land: fulfilled, satisfied and totally “been there, done that, and got the T Shirt” satisfied and completely done with cruising. The average cruising time: five to seven years. Nothing in this life can be done over and over again and retain the initial excitement that was so thrilling at the outset. Cruising and covering thousands of miles is very hard work, and so is maintaining a vessel being subjected to aggressive wear and tear. So, after a few years the initial excitement wanes, the life is not so new and novel anymore, and the sensation of adventure lessens to a large degree. Passages are “just another day at the office.” Going anywhere twice became a total bore. In the end, only brand new horizons could even “move the needle” toward the “emotional adventure zone” again. So in the end, while the hard work never let up, the adventure and excitement waned . . . most particularly on those days when you broke out the tool bag to replace/fix that same part/problem you fixed ten times already over the years. It just gets really old.

As for the reasons that cut the natural lifespan of cruising short, they are the likely suspects that cut any lifestyle short: failures of financial status and/or health status. After the severe economic recession set in two years ago, lack of funds sent many cruisers back to work, even those in their sixties and seventies who thought they were permanently retired. Failing health also sends many cruisers back to shore, and in the most heartbreaking cases, back home to the graveyard. One cruiser we met was happy and having fun and three months later passed away from pancreatic cancer. Any number of these types of risks can end the cruise “out of the blue” and in a matter of days or even hours. You never know. That is why it is so important to take a shot and head out now if you can.

What mistakes did you make in your first year of cruising?

This sounds pretty arrogant, but we did a fantastic job of outfitting the boat, bringing a ton of tools and spares, and we had not one incident or “awakening” that would indicate a “worst mistake” as newbies. We were ready; we went slowly at first; we were VERY patient with weather windows; and, we worked very hard to take every precaution. In our entire cruise of close to 19,000 miles, we never sustained any serious injury, never even scratched the boat, never had any rig problems, never broke down, never got towed in, never hailed for help on the VHF or asked another cruiser for any assistance whatsoever, and never got lost, stuck, or failed to make port safely and on time. I am very proud of that pristine record and until we sold the boat I would never admit it . . . Neptune would have seen to it that my “bragging rights” be taken away instantly with some terrible calamity, and I am sure Neptune is now fuming because I slipped by with a perfect record. It was 1% luck and 99% fastidious preparation.

When have you felt most in danger and what was the source?

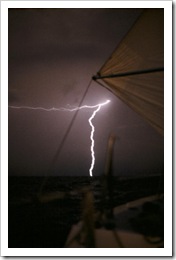

Hurricane Season is the single source of the greatest angst we experienced in all of cruising. The most terrifying event for us was when we were at the island of Bonaire off the north coast of Venezuela and the fastest forming Category 5 hurricane in history (Felix) came very close to us in its early stages. We were lucky and it missed us, but the forecast changed very quickly and a non-threatening forecasted track for the storm changed to a chance it would hit us head on, and we would have lost the boat. Luckily, we were spared, but the winds were over 100 miles per hour only 35 miles to our north when the hurricane passed by. Hurricane season is the Big Bad Wolf of cruising. Insurance policy constraints force cruisers to leave idyllic areas like the Bahamas, Virgin Islands and upper Eastern Caribbean that lie in the hurricane belt, and cruisers must go up the US east coast (and lose all that precious easting they made to get to the Virgin Islands), or hole-up in dangerous places way down south in the Caribbean . . . dangerous as in crime in places like Trinidad, Venezuela, and Guatemala, where Rule of Law is almost non-existent and the murder rates are often through-the-roof, or else hide in places where wicked summer weather is routine such as Panama’s San Blas Islands where epic lightning and rain storms ensue, with striking many vessels per season (sometimes twice!). Hurricane Season, and all that is forces cruisers to do, is the very worst thing about cruising if you ask me.

Share a piece of cruising etiquette

Here are a three of my pet peeves: 1) never, ever anchor upwind and in front of another boat unless you have absolutely no other choice, and if you must do it, immediately take your dinghy to the vessel behind you (or try and hail on the VHF) and introduce yourself; apologize for anchoring “on top of” the other boat, and ask if they are comfortable with how close you are (also, be ready to share how much scope you put out and that you checked your anchor); 2) never, ever tilt your dinghy outboard up at the dinghy dock because it will be a menace to others and their dinghies; and 3) when cruising in a fleet of friends, or anchored in a pack, pick your own “community” VHF channel such as 72 to converse and do NOT use channel 16 to keep hailing each other all day and night. Others on the same passages, or in the same anchorages, want peace and quiet and are most assuredly not interested in all the mindless banter that goes on between the ever-present “radioactive” boats with crews that can’t seem to let five minutes pass without some “diarrhea-of-the-mouth” drivel being chatted about on the radio.

What did you do to make your dream a reality?

I made a no-nonsense, simple, pragmatic “straight ahead” list of what had to be done to really go, and I worked extremely hard to follow the list: 1) buy a boat that my wife picked out and she loves; 2) sell my business; 3) liquidate my home and automobiles and take all that money and buy the boat; 4) accept the fact that our savings will be significantly impacted to fund the adventure and that we will go back to work eventually anyway and pay the price for having gone cruising; 5) outfit the boat quickly to a totally ocean-ready level; 4) take a deep breath, say goodbye, and untie the lines and LEAVE, come what may. It’s so very, very hard to accomplish such a list because the effort involved, physically and especially emotionally, is quite simply astounding. It’s easier to keep delaying things by say “maybe we need another sailing course first” or “perhaps we’ll go after the grandkids are older” or “we probably need more money” or “I don’t want to go until we can retire for good” . . . the list is endless, and usually comprised of layers of fear-based veneers that are all “excuses” and not really legitimate barriers to cruising. It takes a lot of GUTS to “go right at it” and take a list like that and attack it with all your might and not back down, let up, or allow fear and doubt the come aboard for more than a few moments now and then. Knowing what I know now, the biggest impediment to cruising is pure fear of the unknown coupled with the stunning amount of effort it takes to pull it all together. It was one of the hardest physical and emotional endeavors of our lives. It was, predictably, also equally the most rewarding project we have ever accomplished. It’s been said that “no result worth having is easy” and that certainly describes cruising.

Describe a perfect cruising moment that will make cruisers-to-be drool with anticipation

Rather than recite some re-hashed story of a perfect sunrise at sea, or describe that spiritual starlit night watch, I want to paint here with a broader brush. For me the greatest beauty of cruising was the progression of learning what is really important to me. At first, cruising was all about experiencing the beauty of the sea and exotic ports from a tourist's standpoint. As time went on, I was much more interested in the history, culture and the people of foreign lands, rather than just gawking at the natural settings we sailed through (and after a few years those idyllic palm-lined tropical beaches become pretty pedestrian anyway . . . yawn). Then, it was mostly about people more so than the places. I so very much enjoyed meeting so many diverse people, no matter what the setting. And, then as time went on and I interacted with so many diverse people, I began to realize that I was discovering, above all, more and more about myself in the process. People ask “what is the coolest thing you found along the way while cruising” and I always answer: “ME!” Cruising provides one with a priceless experience of freedom to be oneself at all times and settle down and reach a true, unfettered equilibrium of who they really are. That alone was worth the price of admission of cruising.

Can you think of a sailing tip (e.g., sail trim, sail combination) specific to offshore passages (e.g., related to swells)?

Not really. There are so many different boats and designs that there is no generic sail trim tip I can offer. The only “Mother-of-all” offshore tips I can offer is that it has to be the LAW on your vessel: never ever, not even once, not even for a second, not even in perfect conditions, ever go on deck alone without being tethered to the boat. The mission is to come back home alive and if you never break that LAW the odds are you will make it back to home base.

Over the time that you have been cruising, has the world of cruising changed?

Yes, it is changing in many ways. The advent if GPS has allowed more people the ability to cruise farther into more remote areas and do so more safely as to navigational hazards like reefs, etc. Electric winches and windlasses and more sophisticated running rigging has allowed the single-handing and short-crew sailing of larger vessels. Vessel designs are changing too. For one thing, catamarans have finally been recognized as very seaworthy cruising vessels and also as vastly superior platforms for living aboard in the tropics. Ocean sailing itself has never been safer, what with EPRIB’s and Iridium Phones, and technology that can provide instant communication and real time weather information. All of this means that cruising is accessible to a much wider range of people with a much wider range of skills (or lack thereof). More cruisers mean more tourist traps down island, and there is more crime now too. It’s getting very hard to find those truly remote, pristine areas without another vessel in sight. Those “Blue Lagoon” dream destinations are still out there, but with the growing cruising population, in some areas down south cruisers have now moved in, become liveaboards, and are there in such numbers that they obscure the local culture and diminish the authenticity of what once was. Also, it is of note to mention that cruisers are now as diverse as the people in your subdivision back home. They run the gamut all the way from what we all usually envision as “nice folks out cruising” to dangerous criminals and the mentally ill. That is why one should be very cautious about becoming “fast friends” with new acquaintances while cruising. Just because someone lives on a boat does not mean anything at all as to what kind of person they are or whether you should allow them on your vessel or go aboard theirs. When you head out cruising, take you streets smarts aboard with you. Cruising is becoming as much an industry as it is an adventure with both good and bad attributes. Cruising will always be a terrific adventure and I would do it all again, no matter what. All one can do is work hard, be informed, and adjust plans according to one’s own comfort zones. The only way one can really totally screw up cruising is to not do it their way and not have fun. There is no right or wrong way or style of cruising in the end. You get to do it precisely your way. And life does not get much better than that.

I wish everyone great success in getting their adventures underway and in their ongoing cruising efforts!

What question do you wish I would have asked you besides the ones I've asked you and how would you answer it?

"What kind of firearms do you have to protect yourselves?"

The "guns onboard issue" spawns endless, passionate debates and for good reason. Obviously, there are two very polarized schools of thought. As for me, I am a Louisiana sportsman and a keen marksman too. I respect and appreciate firearms and I absolutely believe in the right to bear arms and the right to protect one's self and loved ones. My wife, Melissa, on the other hand, grew up in a Californian family that never owned guns. She is terrified of guns and was very uncomfortable about the thought of having a gun on our boat. Her feeling was that the utility of a gun on board far outweighed the risks it posed to us.

After much research, and after long internal and external conflict, I opted for protective measures that did not include firearms. That is NOT the decision you would have expected from a "Southern Boy" from a politically "Red State" is it? But an objective analysis rendered that result nonetheless. Among the various factors I considered, the shooting of famous New Zealand yachtsman Peter Blake, weighed heavily. While anchored off the Brazilian coast on December 7, 2001, Blake was shot and killed by a band of young pirates. Some critics have argued that Blake's shooting can be attributed to his escalation of a robbery into a "firefight" by resisting the robbers with a rifle.

From the sailing publication

Latitude 38: "

Tragically, Blake's decision to defend his boat and crew probably precipitated his death. If Peter did not arm himself, this maybe would not have happened. The robbers would have taken the objects and left it at that." One of the greatest sailors in the World, Peter Blake's death rocked the sailing community around the globe and the "guns on board" debate reached fever pitch after that tragic incident.

Aside from Peter Blake's murder, I am old and wise enough to know that "successful" gunfights are a fantasy that has been instilled in us by Hollywood! In reality, when guns come into play it will probably end very, Very, VERY badly for all the parties involved, even if you do "win" and "get the other guy."

Also, I read John S. Burnett's sobering look at modern day piracy I his book "Dangerous Waters: Modern Piracy and Terror on the High Seas" (Plume Books, published by the Penguin Group, 2002). Burnett's overview on piracy is dramatic and one comes away with a complete understanding of two main points: 1) all vessels, even Supertankers are successfully attacked by pirates around the world and no locale is immune; and, 2) engaging the pirates in a fire fight is the worst course of action - cooperation and ending the episode as quickly as possible is the only viable course of action.

I have concluded piracy attacks are of two basic types: Type 1: a lone thief (maybe with a buddy waiting for him in a small boat), climbs aboard and tries to steal your wallet or dinghy while you sleep, perhaps armed with a machete at worst. Type 2: a fast boat loaded with four or more well-armed robbers comes along side and they board you (sometimes the crooks are even in official military uniforms, as has happened to boats anchored at Isle De Margarita in Venezuela, for example).

It does not take much mental energy to conclude that it's stupid to try and engage a boat load of seriously armed men, no matter what guns you have on a sailboat. They

will probably outgun you and then your death warrant is signed. As for the machete guy, we ultimately decided we could fight him (and that may not be wise anyway) with pepper spray and flare guns and the like if he tries to break into the boat. In fact, we can just keep the hatches locked and let him have the damned dinghy. That would be better than winding up is some

Third World courtroom.

We were out cruising to have fun. Take it from me as an attorney, engaging the legal system (anywhere in the world), is as far from fun as you can possibly get! Also, aside from guns potentially escalating theft-only situations into deadly firefights, guns on board pose a more likely and imminent risk to the cruisers who carry them. Many countries require a declaration of firearms and often require you to surrender the firearm and ammo during your stay. So, that leaves you unarmed

anyway, with the added hassle of returning to the port of entry to retrieve your firearm when you check out a country.

If you tell a lie about the firearm and don't declare it, you are taking

huge risks. If caught, you could face long prison time and seizure of your vessel and all its contents. Ignorance of the law is no excuse. A couple of years ago a cruiser was arrested, fined tens of thousands of dollars and has been criminally prosecuted in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands for having undeclared firearms on his boat. Virgin Islands Customs and Immigration Officers do not ask about weapons when you check in. There is no question on the written form you fill out. You are just supposed to know! Despite the risks, most cruisers I know with guns simply don't declare them and hope they don't get caught. But, what is the point of that? Who cares if a gun was

hidden successfully? Where is the security in that? The point of having the gun is to be able to

use it successfully for self-defense.

If a hidden, undeclared gun is used to shoot or even merely threaten an assailant in foreign country, then the risks become extremely high for the gun owner. There is no available defense for the gun owner such as: "Well, gee whiz, Judge; I know I didn't declare the gun, but

come on! We were being assaulted and

I really needed to use the gun." That won't fly. In short, if you hide a gun and don't declare it and then use it, you could very well lose your boat and everything on it, plus in many jurisdictions you will find yourself in a Third World jail cell for a long time, probably more than the assailant(s).

At this point in guns-on-boats discussions around campfires and at potluck dinners, the gun-hiding cruisers always retort: "

Well, after I shoot that son-of-a-bitch, I'll just pull anchor and leave!" But that leaves the shooter in a position of always looking back at his wake,

forever. Will a shooting catch up to you? There is no statute of limitations on murder. Will that boat that was anchored next to the shooter's boat give a description of the shooter's boat and turn him in? Will a local fisherman, out dragging nets at night, see you exit the anchorage and give a description?

From another angle altogether, forget everything else and just think only about this for a moment: wouldn't it be tragic if after all the effort it took to go cruising you came away from the entire experience with the act of killing someone being the most memorable event of the whole adventure? It would absolutely reduce the Cruising Dream into nightmarish rubble. So, against the backdrop of all that, I finally came to the conclusion to leave firearms at home and risk being unarmed versus risk being armed, rightly or wrongly.

Nonetheless, the gun issue is very emotional and no clear answers present themselves.When it comes down to it, guns are such a personal choice that my opinion, and everybody else's opinion, is wholly irrelevant to you. You must look at all the different "angles" and decide the gun issue on your own. There are no hard a fast rules. Some cruisers have in fact successfully used guns to fend off attacks and gotten away with it. Some have lost their lives, however, like Peter Blake did after firing the first shot.

Of course, I always feared that one situation where I would never forgive myself for not having brought a firearm. No matter what the consequences would be for me in the end, if I could have totally prevented physical harm to Melissa and failed to do so for lack of a gun, I would be hard pressed to ever forgive myself. Melissa and I talked about all of these issues very candidly, but in the end Melissa did not want any part of a Cruising Life with a gun on board. And so it was for us. The "guns on board" decision is a very personal one indeed and I can offer no real advice whatsoever, other than to share what the process was like for us.

Brian & Mary Alice O’Neill have been cruising since 1987 aboard Shibui, a Norseman 447 (47’) hailing from Seattle, WA, USA. From 1987 – 1989 they sailed through the South Pacific to NZ (on different boat which they sold there). From 1992 to 1997 they completed a circumnavigation (Mexico to New Zealand via South Pacific: French Polynesia, Cook Is.; Niue; Tonga; Fiji, New Zealand. New Zealand to Mediterranean via the Red Sea: New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, PNG, Indonesia, Borneo, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Djibouti, Eritrea, Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain. Atlantic Crossing: Gibralter; Canary Is. to Caribbean. West Coast of Central and North America via the Panama Canal). Since August 2009 they have been cruising Hawaii; Palmyra Reef; Micronesia (Marshall Islands, Kwajalene, Kosrae, Pohnpei, Yap). I caught up with them via email at the end of 2010 in Palau. You can see some of their photos on their web album or contact them via email (svshibui@gmail.com).

Brian & Mary Alice O’Neill have been cruising since 1987 aboard Shibui, a Norseman 447 (47’) hailing from Seattle, WA, USA. From 1987 – 1989 they sailed through the South Pacific to NZ (on different boat which they sold there). From 1992 to 1997 they completed a circumnavigation (Mexico to New Zealand via South Pacific: French Polynesia, Cook Is.; Niue; Tonga; Fiji, New Zealand. New Zealand to Mediterranean via the Red Sea: New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, PNG, Indonesia, Borneo, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Djibouti, Eritrea, Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain. Atlantic Crossing: Gibralter; Canary Is. to Caribbean. West Coast of Central and North America via the Panama Canal). Since August 2009 they have been cruising Hawaii; Palmyra Reef; Micronesia (Marshall Islands, Kwajalene, Kosrae, Pohnpei, Yap). I caught up with them via email at the end of 2010 in Palau. You can see some of their photos on their web album or contact them via email (svshibui@gmail.com).  Describe the compromises (if any) that you have made in your cruising in order to stay on budget

Describe the compromises (if any) that you have made in your cruising in order to stay on budget